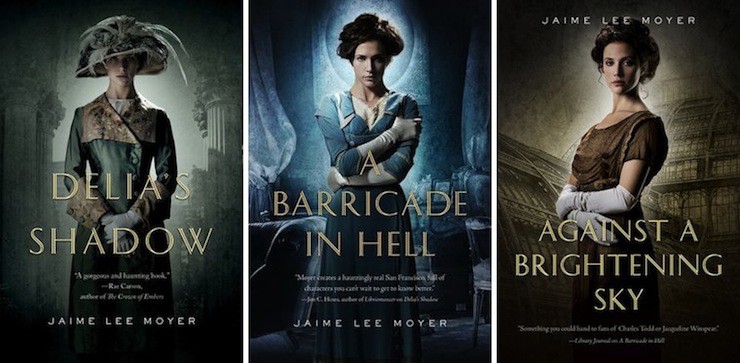

The third volume in Jaime Lee Moyer’s debut trilogy, Against A Brightening Sky, comes out this month. It brings to a close the sequence begun in Delia’s Shadow and continued in A Barricade in Hell. Full of ghosts and consequence, and set in San Francisco in the early 1920s, it’s a fun ride. With murder in.

I thought it might be interesting to ask Jaime a few questions about genre, murder, history, and her attraction to ghost stories. She graciously agreed to answer them.

Onwards to the questions!

LB: Let me start rather generally, as usual, by asking your opinion of how women—whether as authors, as characters, or as fans and commenters—are received within the SFF genre community. What has been your experience?

JLM: The immediate answer that comes to mind is that women are received as barbarians at the gate. It’s a bit more complicated than that simple statement, and there are layers to women’s inclusion in the genre community, but we’re often viewed as invaders. Portions of the SFF community really wish women would go back to wherever they came from and let men get on with it.

Where we came from, whether authors, fans, bloggers or commenters, is the same pool of fans and readers that produce our male counterparts. Women involved in genre today grew up reading all kinds of comic books, sought out books by Ursula LeGuin and Vonda McIntyre and Judith Tarr and Kate Elliot, watched Star Wars and Buffy and X-Files. We dreamed of piloting star ships and slaying dragons.

The idea that women suddenly rose up en masse to suck all the fun out of SFF is just silly. Women have always been a part of SFF. Always.

This is not to say that how women see their role—or some would say their place—in the genre community hasn’t changed over the last ten or fifteen years. I got serious about writing around 2001 and started paying more attention. A lot of that change happened right in front of me.

The internet plays a big part in giving women writers more of a voice in the larger world, and in letting far flung authors—and bloggers—talk to each other. Knowing you’re not alone is huge and empowering. But the internet is a double edged sword. Women who speak up too loudly, or too often, find themselves the targets for some ugly threats.

Women authors have always wanted to be taken seriously, but I think we’re much more vocal about it now. We want our stories to carry equal weight and to be considered as valuable as the stories men tell. We want the heroes we write about, and our children’s heroes, to reflect the people around us. Most of us aren’t shy about saying so.

One thing that has really surprised me since my first novel came out is how much deliberate and determined effort goes into ignoring women authors. I mean, I knew women had to work harder for half the notice. I’ve blogged before about invisible women writers, some of which have been published twenty years or more.

But how entrenched, and wide spread the idea is that women don’t write “real” SF or certain kinds of fantasy was a shock.

LB: Second question! Your novels are set in San Francisco just before, during, and immediately after the Great War. What’s the appeal of this period and setting for you?

JLM: The original idea for the first Delia and Gabe book came with the setting pre-installed. I didn’t fight that instinct or second guess my story brain. Instead I ran with it.

I spent most of my adult life in the San Francisco Bay area. I think of it as home. The house I lived in was only three miles from the Bay, and the Fremont Hills (part of the East Bay Hills) weren’t much farther in the other direction. I used to stand at my kitchen window and watch the fog off the Bay swirl in the streets, or tendrils creep up the hills and fill the hollows. Sound carries in the fog, and many were the nights I fell asleep listening to fog horns.

It’s a beautiful area, rich in history and culture, and incredible architecture. Large areas of the city were destroyed in the 1906 quake and fire, but many many buildings survived almost untouched and stand to this day. Chinatown was rebuilt exactly as it was before the fire. San Francisco’s Victorian houses are world famous.

Getting the setting right, and helping others see what I’d seen, was easier as a result. Not a slam dunk by any stretch, but knowing the area so well was a definite advantage.

I’ve said before that the 1910s, and the Great War especially, have fascinated me since childhood. I couldn’t have been older than ten, maybe eleven, when a friend of my father’s gave him a book about WWI. It was a big, oversize picture book published in 1918 or 1919, and typical of the time in having big chunks of text interspersed with half-page black and white photographs.

These were news photographs, and they didn’t pull any punches. All the horrors of trench warfare, of gas attacks, and artillery shelling were laid out on the pages.

My parents never censored what I read, and I spent hours going through that book. As an adult, I can see the potential of a child being traumatized by the contents of most of the photos. That never happened, maybe because flat, somewhat faded black and white images felt a bit removed from the reality of what they pictured. Maybe I knew even at ten that this was a fragment of history from the distant past, not something I had to fear here and now.

Unfortunately, I grew up and learned better. Human cruelty and how inventive we can be in killing each other, war and slaughter are always to be feared. The fascination with the Great War remained, but changed into wondering how people could do that to each other, and mourning the loss of so many lives.

While WWI casts the longest shadow over the 1910s, it was far from the only major historical event, or societal change, to attract my attention. San Francisco was in the center of much of this change, and the scene for many historic events. Some of these major events found their way into Delia and Gabe’s story.

The Panama Canal opened in 1914 and the Panama Pacific Exposition was held in San Francisco in 1915. Visitors from all over the world flocked to the city for the Pan Pacific, and it became part of San Francisco history.

In 1916, as the U.S. prepared to enter the Great War, a huge Preparedness Day Parade was planned for San Francisco. A suitcase bomb planted near Market Street went off during the parade, killing ten and wounding forty bystanders. Radical labor leaders—characterized in some accounts as “anarchists”—were framed for the bombing, but the real bomber was never found.

What we now call PTSD was known as “shell shock” during the Great War. Not understanding what shell shock was, or how to treat it, was horrible for the soldiers affected, and for their families. This was another new horror gifted to the world by modern warfare.

Labor unions had existed in the U.S. and San Francisco since the late 1800s, but they became more active in the 1910s, holding large parades of their own and becoming more vocal in the process. Business leaders and many politicians equated labor unions with the anarchist movement. Both “Bread, not revolution” and “the propaganda of the deed” were well known phrases in the 1910s. It’s not much of a stretch to say that those opposed to unions, as well as the anarchist movement, saw anarchists under every rock. In a lot of ways it foreshadowed the red scare of the 1950s. At least that’s the way I read it.

And the women’s suffrage movement, both in the United States and England, changed society in untold ways. What women went through to gain the right to vote is hair curling when you dig into it. I could draw parallels to the 21st century wish list of some U.S. politicians for putting women back in their “place”, but that’s another column.

The point is that there is so much almost untapped history to draw on for fiction from the 1910s. While the history isn’t the story, it is the backdrop against which my characters live their lives. I like to believe it makes their story richer.

LB: Do you think it’s important to write fantasy informed by history? Does this hold true for second-world fantasy, too?

JLM: I do think it’s important, whether you deliberately set out to write a story that plays out against a real historical background, or you invent a history for a made up world. There are several reasons for me thinking that.

First, real people like you and me, or the woman around the corner, don’t live our lives in a vacuum, or without some awareness of current events. Most of us are aware of what’s happened in the past. The average person might not have the desire to dig deeper into history than what they were taught in school, but it takes a great deal of effort not to be aware that the world didn’t start the day you were born.

The same should be true of characters. Even as they act out their own personal dramas, wins and losses, in a story, there should be some awareness—however slight—of larger world events, past and present. In my ideal writing world, those events should even impact the character’s lives in some way.

Much as some people—even some authors—want to claim otherwise, history isn’t a blank slate to scribble on at will and rearrange to your liking. I think of history as this huge tapestry woven of multi-colored threads, populated with all different sorts of people, each of them a part of stories of heroes and villains, of wins and losses, and cruelty and kindness.

The catch is that where any one of us is standing, our life experience and the culture we’re raised in, changes our perspective and the story we see. Heroes can become villains, and cruelty can be viewed as justice or retribution. It’s a tricky line to walk when you’re a writer.

I do my very best to keep that notion of perspective in mind when I’m writing. Cultural conditioning is a disease we all carry. The deeper I dig into history when doing research, the more I find that things I was taught were absolute truths—aren’t. Ugly, dirty bits of history—aka the things I wish I’d never learned that give me nightmares—are usually buried deep.

One of the most wonderful things about writing fantasy is being able to write stories from a different historical perspective. There is a huge difference between writing from the viewpoint of a conqueror versus the people enslaved, or driven from their homes. A woman trying to keep her children fed, is going to see events differently than a man who never gives his next meal a second thought.

I’m not talking about message stories, or trying to cram a different worldview down a reader’s throat. But fantasy stories are an opportunity to show readers what it’s like to view the world through a different set of eyes, and a different set of experiences.

Which is not to say I always get it right. But I’m working on it.

LB: So what, or who, would you say has influenced you most as a writer?

JLM: For me, that’s not an easy question with a single answer. The sum total of my life made me the writer I am today, and in all honesty, I never think of influences. I find it nearly impossible to distinguish between “influence” and “teacher.”

Every book by every author I’ve ever read, whether I loved the book or hated it, has taught me something in one way or another. It’s akin to switches flipping in my brain one at a time, or finding the right piece in a jigsaw puzzle that’s mostly blue sky and ocean. Writing influences aren’t a one time, no one will ever influence you again experience. For me it’s an ongoing process.

The books I didn’t care for showed me what I didn’t want to do as a writer, and the kinds of stories I didn’t want to tell. I know it’s a form of heresy in some circles, but I never wanted to write like Jane Austen, or a dozen other revered authors I could name. Their stories never struck a cord with me, or connected with me emotionally. Believe it or not, “Don’t do that.” is a much easier lesson to put into practice than trying to master the skills you admire in others.

Naming names of some of my positive influences: I wanted to grow up and be Ursula K. LeGuin for too many reasons to list. Ray Bradbury showed me that you can tell the creepiest story—and give people nightmares—in deeply poetic language. I will always remember the dark, golden-eyed Martians, the rain on Venus, and lions roaring in the nursery.

Elizabeth Bear and Kate Elliot are a continuing influence in worldbuilding. Neil Gaiman flipped a major brain switch by showing me there is more than one way to write a sentence. Rae Carson and Jodi Meadows taught me about voice, and telling my own stories.

There are others. I don’t think writers necessarily ever abandon their influences totally, but there comes a time you have to take a step away, and tell stories that are yours alone. You find your own voice.

LB: In your trilogy, Delia (one of the main characters) and Isadora see and affect ghosts (and are affected by them in turn). The dead are a major driver of events for the living. So, why ghosts? What’s the appeal?

JLM: Why ghosts is a question I asked myself over and over when I got the idea for the first Delia novel. That book dropped into my head fully formed, complete with a ghost determined to haunt Delia. The ghost wasn’t going away no matter how I poked at the plot, so I decided to make spirits a feature and not a bug.

Spiritualism was still going strong in the 1910s. Nearly everyone, from shop girls to renounced scientists, believed in ghosts and communication with the dead. Mediums held seances in people’s homes to pass on messages from loved ones that had gone on to “the other side.” Trance lecturers were a form of popular entertainment, attracting large crowds to auditoriums and lecture halls to hear messages from their spirit guides.

The more I read about this, the more fascinating it became. I discovered ties to progressive movements back to the mid-1800s, and strong ties to early women’s rights movements. Trance lectures were the first time many American women had a socially-sanctioned opportunity to address a public audience. If the messages their “spirit guides” delivered strongly advocated greater freedom and rights for women, no one could place blame on the woman giving the lecture.

Giving Isadora and Delia the ability to communicate with ghosts fit perfectly with the time period. There would always be skeptics who didn’t believe, but for the most part they could go about their business unimpeded. For someone with real powers, abilities and knowledge, aka the 1910s version of a witch, being seen as a medium was the perfect cover.

I did a lot of research into ghosts and the mythology surrounding them. Almost every culture in the world has a ghost tradition stretching back hundreds, and in some cases, thousands of years. I read everything I could find about phantoms and haunting.

Then I did what I could to make up my own kinds of ghosts, and reasons for why they acted as they did. And I wanted Delia’s dealings with these spirits to be a tiny bit at odds with Isadora’s instant reaction to ban them all instantly, and complicated by her compassion.

One of the themes I wanted to thread through these books was that power brings great responsibility, and that knowing what lurks in the dark, things most people never see, is both a burden and dangerous. Both Delia and Isadora feel responsible for protecting the living, and they both know what failing means.

So that’s why ghosts.

LB: What (or who) do you read yourself for pleasure? Who do you think is doing exciting entertaining work in the SFF genre at the moment?

JLM: Pleasure reading is limited by time, but I sneak in as much as I can. Poetry is my comfort reading, and the easiest to steal odd moments and indulge.

I read a lot of history, not just for research, but because I love it. If some of what I’ve read wanders into my books, all the better. There are so many little tidbits and odd stories hidden in primary historical documents, and in old newspaper archives. I’ve stumbled across amazing stories and real life incidents I couldn’t make up in a thousand years.

While I’m primarily a fantasy writer, I have a major non-fiction crush on science books, websites, and magazines. Doesn’t matter what kind of science, I devour it all. There was a time in my life I read every single book documenting Louis, Mary, and Richard Leaky’s work on the origins of early man, and companion works on how civilization came into existence. Anthropology, paleontology, theories on designing space colonies, robotics—I read all of it. Someday all that science knowledge is going to manifest itself in a science fiction novel.

Fiction reading is almost all science fiction and fantasy, leaning heavily towards fantasy.

I’ll keep my list of who I think is doing exciting work in SFF today fairly short.

Karina Sumner-Smith’s debut novel Radiant was one of the best surprises of the year for me. She sucked me in from the first page and I couldn’t read fast enough. Incredible voice, tremendously entertaining.

Both Karen Memory and The Eternal Sky series by Elizabeth Bear were amazing. Bear’s skills continue to grow and mature.

Fran Wilde built an amazing world for Updraft, and filled that world with compelling characters.

Robert Jackson Bennett not only writes extremely entertaining books, with surprising depth, but they might be the most deeply weird novels I’ve ever read.

I could list more, but I’ll stop here.

LB: What are you working on at the moment? What are your ambitions for the future?

JLM: I have two major writing projects in the works right now and a slew of minor projects.

One is a new novel titled A Parliament Of Queens. Set in a secondary world, this is the story of Rosalind, the alchemist Queen of Kenor, Maryam, the Radiance of Alsmeria, and Sofija, Empress of Dalmatia, three princesses who suddenly find themselves monarchs of their respective nations when all the male members of their families are assassinated. And it’s also the story of Owen, Rosalind’s spymaster, chancellor, lover and life partner.

I think of this as an art deco world, full of magic and alchemy, and one that contains both the strange and familiar. The technology level is about real world 1930s, and airships have untied the continent in much the way railroads tied continents together in the history we know. I have some ideas on how to remake those airships into something fairly unique, and maybe slightly terrifying. And some of the magic is flat out creepy, but this is me.

The other major novel project is rewriting The Brightest Fell, a novel set in a Sherwood Forest full of magic, Fae lords and ladies, and a dragon guardian at its heart. Marian is the Witch of Sherwood in this book, raising her two children alone, and Robin is far from a hero.

I wrote this book around the time I wrote Delia’s Shadow. Then I set it aside because I knew in my bones I didn’t have the writing chops to do the story justice. Now I think I do.

Minor projects include two novellas (if I can keep them from transforming into novels), some short stories, and then there are the YA projects I want to finish. We’ll just say I won’t be bored.

Personal ambitions for the future are to sell more books, and tell more stories readers fall in love with. None of that is a sure thing, but I’m going to give it my very best. A person never gets anywhere in life unless they try.

I have other ambitions as well, all of which revolve around women in genre as a whole. Helping to build a network of women writers, reviewers, bloggers, and commentators to bring more attention to women’s books and stories is a personal goal. Women write almost half the genre novels published each year, and get a fraction of the promotion and attention. Call me Pollyanna, but I firmly believe that women working together can change that. It won’t be quick or easy, but it will happen.

I’m fully aware that there are some who will see this as a vast conspiracy, but it’s not anything men haven’t done for decades. And one person’s conspiracy is another woman’s support network.

The future is a far country, full of wonders. There’s room for all of us.

Liz Bourke is a cranky person who reads books. Her blog. Her Twitter.